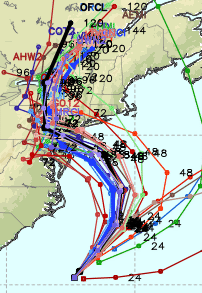

This graphic, from Mike Smith’s blog, may look like a jumble to you. But to meteorologists, it’s a thing of beauty. It’s a so-called spaghetti chart or diagram (wonder where they got that name?) made by juxtaposing different numerical forecasts… in this instance, for the track of hurricane Sandy back in October of 2012. A given ensemble of such forecasts may be created from a single numerical weather prediction model by introducing (slightly) different initial conditions, or may be created from different, independent numerical models, run by different countries and institutions. Depending upon the meteorological conditions and the particular approach used, the spaghetti charts can look far wilder, and the individual possibilities far more discrepant. However, analysis of such a full array of possibilities provides forecasters a means of sharpening their forecasts while at the same time affording them insight into the forecast’s uncertainty.

This graphic, from Mike Smith’s blog, may look like a jumble to you. But to meteorologists, it’s a thing of beauty. It’s a so-called spaghetti chart or diagram (wonder where they got that name?) made by juxtaposing different numerical forecasts… in this instance, for the track of hurricane Sandy back in October of 2012. A given ensemble of such forecasts may be created from a single numerical weather prediction model by introducing (slightly) different initial conditions, or may be created from different, independent numerical models, run by different countries and institutions. Depending upon the meteorological conditions and the particular approach used, the spaghetti charts can look far wilder, and the individual possibilities far more discrepant. However, analysis of such a full array of possibilities provides forecasters a means of sharpening their forecasts while at the same time affording them insight into the forecast’s uncertainty.

Given the power of ensemble forecasts, you might think that meteorologists might favor a similar approach to policy formulation. Surely it would be advantageous for policymakers to have opportunity to take draft legislation before the public and solicit a full range of individual and institutional views. The feedback could delineate between areas of consensus (where the country is united) and where opinions are widely divergent (where we’re polarized). Something like that of course actually occurs in the hurly-burly of politics, on subjects as fractious and momentous as abortion, gay marriage, immigration, social security, health care, gun control, and much more, and on subjects where we’re relatively united, as for example with respect to support for men and women in uniform.

But that kind of free, open voicing of different views doesn’t seem to be what some meteorologists want. Here’s a current example. Back on June 18, Congressman Jim Bridenstine (R-OK1) introduced a bill entitled the Weather Forecasting Improvement Act of 2013 (H.R. 2413). The bill calls for NOAA to reallocate climate research resources to severe weather prediction research. It’s prescriptive in additional respects, speaking to investments in computing power and its application, and the relative roles of public and private sector. It even singles out Observing System Simulation Experiments (OSSE’s) for special emphasis, apparently with an eye to prioritizing contemplated investments in costly Earth observing systems. It refers as well to needed social science, but looks to NSF, not NOAA, to provide needed resources.

The bill has occasioned a flurry of discussion in the meteorological community. So far so good. But some have decried the failure of the community to develop a coherent viewpoint with regard to the legislation and whether and/or how it might be constructively amended and improved. E-mail inboxes are filling up. There’s a notion afoot that somehow the fact we don’t speak with a single voice is a flaw.

It’s unclear that diversity of opinion about this bill, even across our small and relatively homogeneous community, is a bad thing. Surely among all the players… the different agencies and the scientists of different disciplines and the private-sector meteorologists from companies large and small… a range of opinions is understandable. In fact, it might even be that the diversity in our community’s views with respect to policy is a strength (one of many, actually). That’s certainly the idea we have when we approach our bread-and-butter task of weather prediction.

To carry the idea a step further, most meteorologists would agree that ensembles of forecasts from several models, sharing the same basic science but constructed independently, offer a more potential for getting at the best forecast than those ensembles constructed from the same forecast model but with slightly differing initial conditions. [In this latter case, any idiosyncratic model biases would be inherent in all the forecasts.] In the same way, it might be that we could expect better policy guidance when the views of the science community come in to the Congress through independent means… from different companies and universities, from individuals or uncoordinated consensus-building in multiple, informal, ad hoc small groups… some coming in from e-mail, others from phone calls to staffers, or possibly a direct aside from a scientist to a member or two of Congress itself. It might be that this approach, which seems laissez-faire, almost casual, actually leads to superior outcomes.

For that reason, scientists should be skeptical of any efforts by their professional organizations to mount mass mail-ins to members of Congress on legislation. The members easily recognize such efforts for what they are and discount them appropriately. Suggestions that scientists think and act in lock step on complex issues, however obvious the policy solution may seem, don’t make best use of scientists’ power of thought or serve scientists well.

Today’s example concerns legislation with respect to weather forecasting, but the same arguments apply to climate change science and policy, hazards policy, and policy formulation with respect to resources: food, water, and energy, for example.

Let’s have the energy and wisdom to develop our own viewpoints, the courage to express them, and the love and self-confidence to accept the views of others. Meteorologists can and should take the lead here.

After all, we’re the people of the ensemble.

Great column, Bill. I wonder if it would be possible to do policy maps like weather maps, and then track policy preferences the same way you track hurricanes. For example, after Sandy Hook, a storm brewed in DC aimed at stricter gun control laws. After a few days, it veered away toward tighter background checks, then more or less petered out without affecting much change.

John, this is a really great extension of the idea. The result in the case of the gun control argument was disappointing, but it’s nevertheless part of living on the real world.