The previous LOTRW post focused on the growth and importance of AI to the meteorology and to the AMS 2024 Annual Meeting. To recap:

The rapid growth of AI’s capabilities and reach are transforming research and science-based services in meteorology, climatology, oceanography and the other geosciences. And that reworking isn’t trivial. AI is not merely augmenting the use of physics to generate weather products and services; in some cases it is supplanting them[1].

But it’s not just the supply side of meteorological sciences and services that is changing, and in this way. The demand side is being utterly transformed as well. Historically, the application of meteorological information to guide weather-sensitive economic sectors comprising agriculture, energy, environmental protection, public health and safety, transportation, water resource management and more has been limited by two factors. First, the rudimentary forecast skill of the past often failed to meet sector-by-sector requirements for useful decision-making. But second, sector-by-sector decision-making wasn’t particularly nimble. Given the weather sensitivity, and limited ability to do much about it, weather-sensitive sectors had over the years developed muddle-through approaches – especially the build-up and maintenance of the excess capacity and operating margins needed to accommodate weather variability. More recently, however, population growth and economic pressures have made such excess capacity a luxury no one could afford.

Enter technological advance. Technology generally, IT, and artificial intelligence in particular are transforming the economic world. Along the way, they’re transforming weather-sensitive sectors, making them more agile: better able to incorporate weather variability into their optimization strategies – to capitalize on opportunities offered by favorable weather, and avoid the risks posed by hazards, etc. The emergence of renewable energy sources harnessing solar, wind, and hydrologic power exemplify this trend.

[What follows is conjecture, offered in the spirit of Charles Darwin’s quote to the effect that false views cause little harm to science because everyone takes salutary pleasure in proving them wrong.]

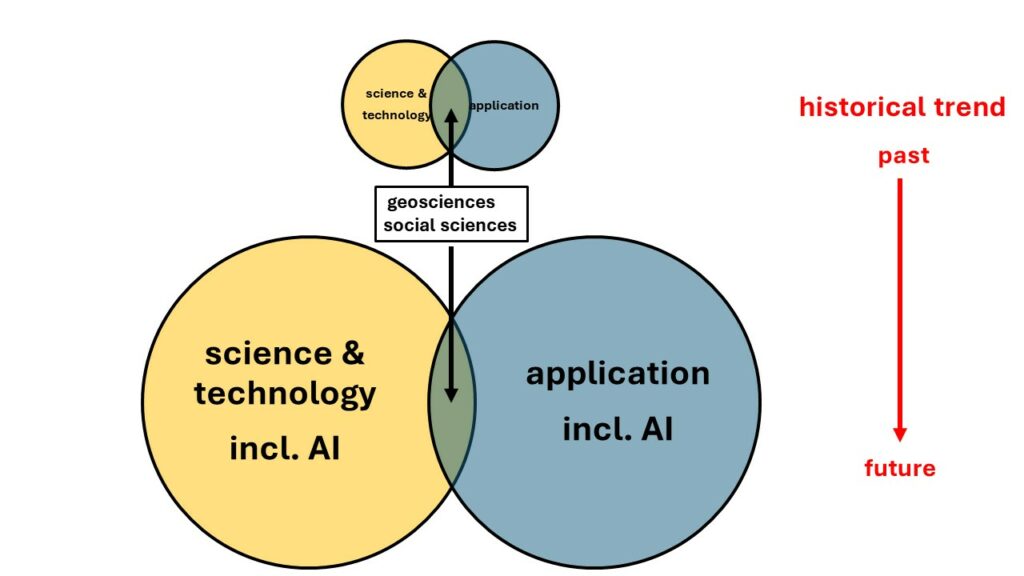

It seems to me that these trends in supply push and demand pull have been and are continuing to transform the AMS Annual Meetings (and the AMS as a whole, and the field more generally) in a way captured by today’s Venn diagram. AMS meetings focus on the advance of “meteorological” sciences (writ large – really the whole of the geosciences) and associated technologies, and their application for societal benefit[2]. That latter bit has come to mean that the AMS and its meetings also encompass and reflect the advance of social science that both studies and enhances societal uptake of meteorological science. But these disciplines are merely the intersection of the two main elements of AMS Meetings, and the Venn diagram: S&T and application more broadly.

The entire Enterprise is growing rapidly in size and in its importance to the larger world. But in the last decades of the 20th-century, a disproportionate amount of the growth of the field and the AMS Annual Meetings in particular came from IT. That trend is continuing now – with AI providing a huge new burst. The geosciences and related social sciences are growing as well; after all, they’re also augmented by AI and technology (as well as other trends). But they’re not growing proportionately; the intersection is a smaller part of today’s meeting.

In short, meteorology and social sciences are struggling to keep pace. This was reflected, for example, in the number of AMS talks focused on the rise of AI-enabled forecast techniques that sidestep rather than build on basic meteorological physics, and remarking that evaluation of such approaches was both lacking and sorely needed. We’re likely entering an extended period of catchup.

This is not a bad thing! It’s to be celebrated! The world urgently needs a new vision and new capacity to cope with growing demands for food, water, and energy, and the accompanying threats to the environment, habitats, and ecosystems.

But scientists of all stripes like to think that science leads the way – that scientific advance fosters technology, which in turn is then applied to meet societal needs. This happens some of the time. But science can also be a laggard.

We can take comfort from the fact that this phenomenon is not new. In the second half of the 19th century most developed countries established weather bureaus, not because of any great new theoretical breakthrough, but because the Victorian internet – the telegraph – enabled the world to track weather in real time. The scientific insights would come later.

This reality doesn’t hold true only for the geosciences. Early in my career (and before most of you were born), the military conducted Project Hindsight, looking at the role of science and technology in contributing to the military systems and weapons developed and use to effect in World War II. Science was found to be pivotal in only a small fraction of the cases examined; 90% were technological. Scientists of the time took umbrage at this. Yet the overall conclusion was positive – that S&T were among the best investments of the war effort.

The forecast? Expect AMS meetings (and AMS journals, and AMS membership) to grow dramatically over the next 5-10 years. Expect the overall vibe to be positive and energetic. Expect rapid world uptake of our science and technology. But don’t be surprised if meteorology and the social sciences as you learned them are slowly submerged as the topic of conversation, in much the same way and for many of the same reasons that machine programming language isn’t the focus of the meetings.

The world is begging: please keep the progress coming!

[1]Some (not all) current AI approaches are exploring the feasibility of ignoring the governing mathematics and physics entirely. The attitude seems to be: if the difficulties of the N-S equations are daunting, we’ll just go around them. Years ago Laura Furgione, then NWS Deputy Assistant Administrator, raised academic hackles at a UCAR-AMS-AGU heads and chairs meeting when she suggested that operational forecasters might no longer need to know calculus; that algebra (closer to the language of digital computers) would suffice. Calculus would be necessary only for researchers. The idea, which seemed so revolutionary at the time, now might be considered mundane.

[2] Essentially the AMS Mission.