“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”– Theodore Roosevelt

Late last week brought a phone call from Paula and Franco Einaudi, friends of many years, with news that wasn’t unexpected, but was nevertheless unwelcome. They’d just learned that Colin Hines had passed away on August 30. During his very productive lifetime, Colin was a scientist of extraordinary gifts. But the loss for us was also personal. While on faculty at the University of Toronto, Colin had supported Franco’s postdoctoral work. A few years earlier, when Hines had been at the University of Chicago, he’d advised my Ph.D. research. Throughout our lives, but especially during our early careers, Colin had been good to us as well as good for us. The same held true for his nurturing and equipping of his other postdocs and graduate students (George Chimonas and Dick Peltier come especially to mind). We mourn his loss; we celebrate his legacy.

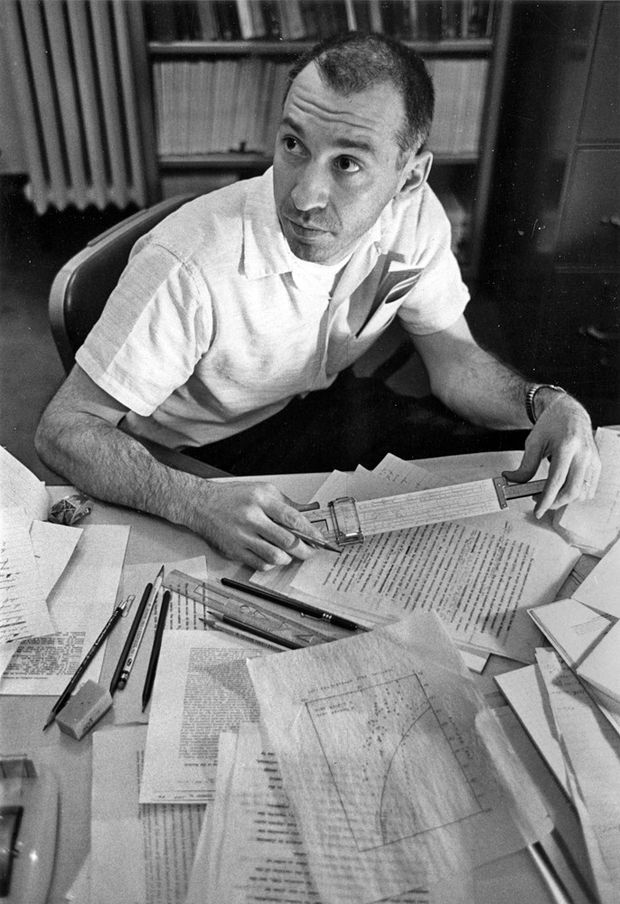

For a few of the basic facts, you might read this obituary (with a mid-career photo) on September 2 from the Toronto Star. Several days of personal reflection over this Labor Day weekend has prompted these (admittedly fragmented) additional vignettes:

Colin the scientist. Colin’s scientific work concentrated for the most part on the Earth’s ionosphere and magnetosphere[1]. With the regard to the former his major contribution was the discovery that internal atmospheric gravity waves generated in the lower atmosphere could account for much of the fine scale dynamics observable in the upper region. With regard to the latter he and a colleague, Ian Axford, developed a theory of magnetospheric convection – a conceptual model of the general circulation of the magnetosphere as driven by the interaction between the sun’s heliosphere and the Earth’s magnetic field. This accomplishment compares to Hadley’s 18th-century discovery and characterization of the cellular structure of the tropical atmosphere in response to solar heating that today bears Hadley’s name. These discoveries have each withstood the test of time while serving as portals through which future researchers could enter the field and make myriad additional contributions.

The man in the arena. Throughout his career, Colin embodied Roosevelt’s admired “man in the arena” – down to every last bit of valor and the accompanying dust and sweat and blood. Educated at Cambridge, he exhibited that Cambridge cultural mix of raw intelligence combined with mental quickness that make the tribe so formidable – sometimes even terrifying – at scientific workshops and conferences. (Think Richard Scorer, Owen Phillips, Francis Bretherton, Michael McIntyre, Tommy Gold, to name just a few I saw in action personally over the years; it’s as if somewhere along the line they’d misheard Descartes to say “I debate, therefore I am.”). One particular moment from an AGU meeting: George Chimonas and I were settling in for a talk when Hines appeared. He said something like “This paper is rubbish from beginning to end. But I have to go across the hall to hear a speaker in a different session. Take care of this guy.” George and I sat through the talk. Sure enough, it wasn’t great shakes, but suddenly during the Q&A Hines reappeared at the back of the room. He caught our attention and gave us a glance as if to say “well?” We shrugged our shoulders. He frowned, raised his hand, proceeded to ask the speaker to show particular slides shown during the talk (how could Hines have even been sure they were there?), and off the cuff gave a different interpretation of everything from the data to the math. Incidents like this weren’t limited to the momentary; some of them were milestones in prolonged controversies that threaded through the literature and technical meetings for years.

That carried over to the politics of science – not the role of science in politics, but the politics of science played out among the oversized personalities of the scientific community. Colin, a Canadian citizen, had been fairly quiet on such matters during his time in the United States, but upon his return to Canada in 1967 he threw himself into that fray with gusto.

This same man-in-the-arena spirit extended into every conceivable realm. A University of Chicago vignette: His students had entered ourselves as a team in the graduate school intramural basketball league. We were mediocre-to-poor; one evening we were short a player, and Colin volunteered to join. What could go wrong?

Our opponents that night were from the business school (today’s Booth School).

They beat us 70-12.

Worst of it was that Hines took an elbow to the eye, opening a cut that required stitches. Later on, when with him or looking at photographs, I could always see the small scar…

When it came to investments, Colin wasn’t content with balanced index funds or any of that tame stuff; he preferred a much more hands-on approach and developed and applied his own theoretical understanding to the financial world – accepting the ups and downs that brought. He appreciated the arts and literature, but didn’t stop there; he wrote a few novels. At every turn he’d see something, and then try it.

In short, Colin was a force. Sometimes there was a price, not just for him. There would be collateral damage. But on balance, his influence was overwhelmingly positive. And all of us around him constantly had to up our game. He made us better, stronger, more thoughtful.

Colin the gracious. And he could be kind, not just about the small things but the big things. Two of these made a huge difference in my life.

I had graduated from Swarthmore College in 1964, and spent my first year at Chicago as a research assistant (RA) in the physics department, preparing for a career in solid-state physics. I then made the switch to geophysical sciences over the summer of 1965. Hines was kind enough to offer me an RA. He didn’t assign me any duties at first. After a couple of weeks I went into his office and said as much. He looked up at me from his desk, and said (with the merest hint of a smile? Hard to tell), “Look, I’m happy to support you. But I don’t want to spend my time thinking of ways to keep you occupied.”

He didn’t have to tell me twice. I’d spent an RA year in the physics department, knocking myself out with my fellow graduate students to make our faculty look good, and going home each night struggling to find the hours and energy to study a bit. I could see the same thing going on with other graduate students in the geophysical sciences. Hines was telling me in effect I had a fellowship.

From that point on, I’d have walked through fire for him.

Then, the second: early in January of 1967 I took my qualifying exams. In the oral phase I wound up talking at cross purposes with Gene Parker (discoverer of the solar wind). Although I passed, the experience did not augur well. A couple of months later (March, April?) I gave Hines a progress report on the start to my thesis research. After a day or two, he called me into his office, and said, “Looks like you’ve broken the back of the problem.” He went on,“Should mention, I’m leaving Chicago at the end of this spring quarter to take a position at the University of Toronto. So why don’t you finish up? Oh, and by the way, Parker is on sabbatical in Greece right now. If you do finish, we’ll have to substitute someone else on your committee.”

!!!

Every other faculty member I’d ever seen or heard of would have been saying to me more like, “so why don’t you pack up, move with me to Toronto, and start out all over again?”

Again, he didn’t have to tell me twice. I shelved sleep (to such an extent that after one 40-hour stint without I convinced myself that there was a “sleep barrier,” a point beyond which you didn’t get any more tired, and I had broken through it[2]) and hammered out the thesis. I defended just before the end of the spring quarter. David Atlas, the radar meteorologist, who’d been on the University of Chicago faculty only a few weeks, replaced Gene Parker on my committee.

There’s much more, but you get the idea. Colin was a man of passion, in every aspect of his life, but especially when it came to his family – his wife Bernice and his children. That was evident at Chicago, when the kids were small, but during our all-too-brief and sporadic encounters over ensuing decades, he was always full with stories of his kids and their diverse accomplishments, bursting with enthusiasm and pride.

Colin, thanks for entering the arena – and especially for inviting us to join, and in some cases pulling us in! We love and miss you.

[1]Loosely speaking, the ionosphere comprises the air above heights of 35-40 miles or thereabouts. That air is rarefied. For the sake of comparison, the air at the top of Mount Everest (five miles) is only a third as dense as air at sea level. Go up another five miles and the air is only a third of that again; essentially a tenth of the air density at sea level. The total air mass at ionospheric levels is only a thousandth of the mass of the atmosphere as a whole. At or above those heights, the molecules of the air are not protected from the most energetic solar radiation, which strips electrons from the molecules. And still further up, above 200 miles height, virtually all the molecules are ionized, and their motions are constrained by the Earth’s magnetic field as well as the pressure forces familiar here on the Earth’s surface. This highest region is known as the magnetosphere; it extends out a few Earth radii sunward; in an extended tail, many Earth radii in the opposite direction.

Meteorologists make much of the dynamical complexity of the lower Earth’s atmosphere. The problems posed by weather prediction inspired the very notion of chaos theory. But ionization adds a raft of additional equations and additional layers of complexity to the prediction problem (something like advancing to higher levels of any online game). Colin was singularly adept at working these more complex problems.

[2]Fourteen hours later, I awoke… that’s living on the real world for you, versus fantasyland.

What a luscious review of a well-lived life. Thank you, Bill Hooke, for this advanced lesson in graciously honoring someone who contributed to your life.

Bill, I enjoyed your rem·i·nisces; they brought back many memories. Colin certainly brought out the best in us. His insistence on rigorous thinking about problems has stayed with me throughout life. I had a similar experience as you with Eugene Parker on my committee and as with you he was absent for the orals; so Colin grilled me on Parker’s topics similar to what had put been on the writtens.

I wasn’t aware that Colin had passed away. I’d been wondering about him in mid-summer and did some quick searching so I’m glad you posted both the information and that you included wonderful memories. They were good times.

Thanks so much for this comment, Bill. Great to hear from you even under these circumstances. Continuing best wishes to you and Betty Jo.

I only just saw Colin’s obituary. I am sad to see it, but glad to have known the man. I first encountered him as an undergraduate physics student at U of T. He was teaching the 2n year course on Waves. He handed out a set of 20 pages of notes at the start of the course and said “Here is everything you need” and said that lectures would be supplementary material. Yet, his lectures had 75 % attendance, as he talked about “whistlers” and other fascinating topics, and had us derive the basics of gravity waves in a problem set. He had planned on having an in-class mid-term and an in-class final test, but we never had the mid-term. We got to the last week of the term, and on the Monday, Colin handed out a test with two questions. “Do one of two” was the instruction. On Wednesday, he handed out the same test and said “Now do the other one”.

Later, as a Master’s student, I took his graduate course on Atmospheric Waves. In the first class, he announced that everyone would get a B+, and so we could simply relax and talk about the science. He added that if anyone wasn’t happy with B+, he would gladly set a test we could try to pass. Of course those were the days when a B+ would not sink your chances at a scholarship.

He was always one of my favourite lecturers and teachers. His kind is rare and will be missed.

:Many thanks, David, for your comment and taking time to share these very poignant remembrances. What a grand collection of stories! Best wishes!