Every generation gives a name to the age they live in.

Of course it’s not quite so simple. Generally speaking, we don’t engage in a naming contest. Rather we all live out our lives in a certain way, and according to the events and accomplishments and failures and the nature of our times, the generations who follow, looking at our impact on their lives, assign us a title. Sometimes the name is good: the Renaissance. The Age of Reason. Sometimes it’s neutral or ambivalent: the Stone Age. The Iron Age. The Age of Exploration. It can also be negative: the Dark Ages.

It’s possible, perhaps even common, for an age to have multiple names. And though we don’t get to vote for names we like, we do find plenty of suggestions on offer these days. To test this, I just googled the unfinished expression “The Age of”. Turns out that through an accident of timing, every entry on the first page referred to the movie, “The Age of Adaline.”

Hmm.

Ah. The second page of entries started to give me what I was looking for – a lot of book titles: the Age of Love. The Age of Empire. The Age of American Unreason. The Age of Access. The Age of Missing Information. The Age of Answers. The Age of Dignity. Dozens more appear on subsequent Google pages. Of course few, if any, of these will endure.

Here’s a candidate for you to think about today: the Age of Global Renewal.

What prompts me to put this forward despite the surfeit of alternatives? The juxtaposition of two articles in the May30th-June5th print issue of The Economist. The first was a cover story entitled The Weaker Sex: no jobs, no family, no prospects. The article tells us something that we already know: blue-collar, poorly-educated men in rich countries are in trouble. They have not adapted well to trade, technology, or feminism. Here’s an excerpt from the web version:

At first glance the patriarchy appears to be thriving. More than 90% of presidents and prime ministers are male, as are nearly all big corporate bosses. Men dominate finance, technology, films, sports, music and even stand-up comedy. In much of the world they still enjoy social and legal privileges simply because they have a Y chromosome. So it might seem odd to worry about the plight of men.

Yet there is plenty of cause for concern. Men cluster at the bottom as well as the top. They are far more likely than women to be jailed, estranged from their children, or to kill themselves. They earn fewer university degrees than women. Boys in the developed world are 50% more likely to flunk basic maths, reading and science entirely.

One group in particular is suffering (see article). Poorly educated men in rich countries have had difficulty coping with the enormous changes in the labour market and the home over the past half-century. As technology and trade have devalued brawn, less-educated men have struggled to find a role in the workplace. Women, on the other hand, are surging into expanding sectors such as health care and education, helped by their superior skills. As education has become more important, boys have also fallen behind girls in school (except at the very top). Men who lose jobs in manufacturing often never work again. And men without work find it hard to attract a permanent mate. The result, for low-skilled men, is a poisonous combination of no job, no family and no prospects.

Chances are, whether male or female, you’re already painfully aware of this problem. That said, The Economist provides a great articulation.

You might well be saying, Problem solved, Bill. Let’s just call this age The Age of Male Decline and be done with it.

You can certainly go that route. And history may prove you right. But pause for the moment and consider another trend, captured in another article, Rus in urbe redux.

Ignore the Latin pretensions. The article is about cities in decline. We all know that the world’s major cities are hovering up rural populations and swelling in population. But the exodus isn’t just from the countryside. It’s from also from relatively large numbers of smaller urban centers. An excerpt:

In Leipziger Tor, people are giving way to grass, flowers and potatoes. So many prefabricated 1950s apartment buildings have been razed in this working-class district of Dessau-Rosslau, a city in eastern Germany, that the plants receive all the light and rain they need. And the local planners have other buildings in their sights. Some residential blocks are half-empty. An abandoned school is succumbing to weeds. They too will probably be demolished and replaced by meadows.

Many of the world’s cities are having to cope with rapid growth. Dessau-Rosslau’s challenge is to manage decline. Since 2007 its population has dropped by almost 10,000, to 81,500. Everybody, from the city authorities to the man in the street, reckons the trend will continue. What will Dessau-Rosslau be like in ten or 20 years’ time? “Smaller,” says Rolf Müller, a longtime resident, as he carries a box of groceries out of an Aldi supermarket.

The condition from which Dessau-Rosslau suffers is increasingly common. From 1950 to 1955 only ten of the world’s largest conurbations lost people, according to the UN (see chart). The tally rose steadily over the next few decades, before jumping in the 1990s, as the collapse of communism in eastern Europe and Russia was followed by a colossal migration. Today just over 100 conurbations are losing people. But this greatly understates the scale of urban decline. In many countries, big cities with diversified economies are growing at the expense of cities too small to make the UN’s list. Germany has 107 autonomous cities, of which 60 are expected to contract over the next five years. But almost all of the biggest cities will escape decline (see map).

Shrinking cities can be found in the post-industrial rustbelts of the American Midwest, eastern Europe and northern England. But the phenomenon is increasingly Asian. In Japan 20 cities with more than 300,000 inhabitants each declined in population between 2005 and 2010. The two largest cities in South Korea, Busan and Seoul, are both contracting. Even rapidly urbanising countries like China and India have a few declining cities. In 2008 the UN estimated that one in ten emerging-world cities were losing people. The only part of the world where shrinking cities are almost unknown is sub-Saharan Africa. But that too will change.

A city can lose some people and barely notice. It might even have to build more homes, since in many countries more people are living alone. But persistent decline is harmful, especially if the population is ageing as well as shrinking. As factories and homes are abandoned, the local economy can spiral downward.

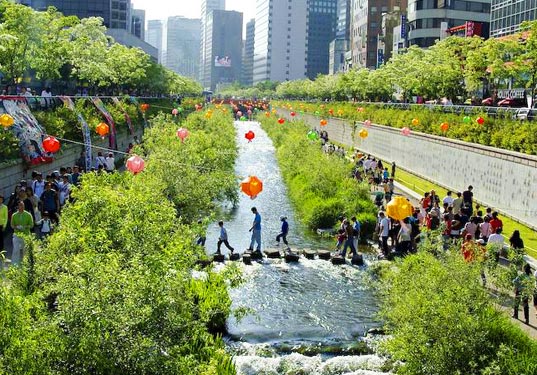

The body of the article (worth the read) goes on to point out that efforts to stem such declines through the creation of special economic zones, etc., rarely succeed. However, the article cites instances in which demolition of decaying urban areas and the restoring the land to parks and more natural landscape has actually improved the prospects for the downsized urban areas remaining.

So here’s the thought. The nature of such demolition and restoration is inherently labor-intensive and physically demanding. It’s also inherently local, place-based work. It can’t be outsourced to another, distant country, as can the manufacture of textiles or computer chips. Such work is therefore in principle available virtually everywhere.

Well and good, Bill, but who’s going to pay for it? Great question. Millennials are too young to remember this, but those of us of a certain age can recall when the same question was asked of recycling. When separation of trash and recycling of paper, plastic, and metal goods was introduced in the last century few thought such efforts would pay or prove sustainable. The fact is, that the practice has spread.

There is low-hanging fruit here. We know all too well that the world’s poor are forced to live on dangerous seismic faults, floodplains, and unstable slopes. This and our practice after natural disasters of “rebuilding as before” condemns us to repetitive loss. It also perpetuates pockets of poverty: the social science shows that growing economies recover from hazards, but stagnating economies do not. Disasters aggravate pre-existing economic trends.

Nations, cities, and localities able to think long-term might therefore recognize that the cost of returning decaying urban land to nature can be recovered from the reduced future costs of natural disasters and social unrest. It’s therefore easy to imagine social engineering of this sort becoming widely accepted, intentional policy, making such restoration a way of life for, say, the rest of this century. (And, in the process, taking its place alongside rebuilding and maintaining critical infrastructure as an important societal goal accomplishing similar ends.) Note that we’re not insisting society do a 1800 turn; we’re only embracing what’s already underway here and there and scaling it up.

The Age of Global Renewal? Should have a much better ring to it than The Age of Male Decline, whether you’re male or female.

Nice try, and wish it would be true!

But our age will only be named after we’ve lived through it, and the way we’re going it likely will be something more like the Age of Muddle. Our political processes – bogged down in confused bickering. Our economy – a fragile yo-yo, with central bankers floundering around because they have no experience with this set of circumstances to light their way. Our society – splitting along an educational divide, with the Educated flourishing, the Uneducated living in increasing isolation, and the Great Middle muddling along.

At the same time we are warned that global warming threatens our food supply our food production is not only steadily increasing but has actually accelerated this century. While we can send messages around the world in seconds, our ability to communicate with one another is eroding. And while resources are more abundantly spread around the world than ever before in recorded history, too often we lack the will and the wisdom to use them. An Age of Muddle, indeed.