The Earth sciences community lost one of its most luminous, influential lights on June 27th, with the passing of Francis Bretherton. The Webster-Kirkwood Times, a newspaper from the area near St. Louis where he had lived out his final years, did a respectful, crisp job of presenting the essentials. Here’s an excerpt:

Francis was born in Oxford, England, in 1935, to Russell and Jocelyn Bretherton. In 1953, he met his future wife, Inge, while he was a high school exchange student in Munich, Germany. They were married in 1959.

After receiving his doctoral degree in fluid dynamics from the University of Cambridge, he became a Lecturer at Cambridge and a Fellow of King’s College, embarking on a career of pioneering research into geophysical fluid dynamics. In 1969, he moved to The Johns Hopkins University as professor of earth and planetary sciences. In 1973, he was invited to serve as president of the University Corporation of Atmospheric Research and concurrently director of the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, positions he held until 1980.

In 1983, he chaired an interdisciplinary committee of scientists to advise the U. S. government on Earth-related research priorities. Two seminal reports by this “Earth System Science” Committee (1986 and 1988) presented a multidisciplinary vision of the Earth’s environment and climate as a set of interlinked components. The Committee’s recommendations led to a presidential initiative in 1989 to establish a still ongoing U.S. Global Change Research Program. It also facilitated NASA’s development of an Earth Observing System from space.

In 1988, Francis became director of the Space Science and Engineering Center and Professor of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His work won him widespread recognition, including awards from the Royal Meteorological Society, the American Meteorological Society, and the World Meteorological Organization. He mentored an impressive group of graduate students, who went on to influential careers of their own. Francis retired in 2001. He and Inge continued to live in Madison. while enjoying travel, classical music, and the outdoors. In 2017, he and Inge moved to St. Louis to be closer to family…

If you’re one of the thousands of scientists, engineers, graduate students, or climate-service providers who are or have been supported in part by the $40-50B that the federal government has invested in the U. S. Global Change Research Program over the past three decades, you owe a debt to this man. Fact is, all of us do. Billions worldwide stand to benefit from actions underway to mitigate or adapt to climate change – actions pursued with greater vigor and purpose today because of work he helped inspire.

Some personal reflections:

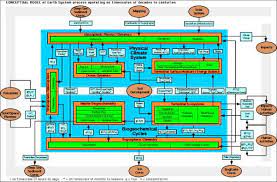

Start with raw intellect. We’ve all met bright people in our lives. In many, maybe even most cases, they’re very bright. But most people who’d ever met Francis would include him in their top ten. Maybe their top five. Maybe the brightest. Take this figure:

When Francis introduced this in the 1980’s he referred to it as a conceptual diagram of the Earth system. (Conceptual? Really? To most of us at the time it looked like an unfathomable rats’ nest. The diagram was definitely an acquired taste.) Today it’s known as the Bretherton diagram.

As it happens, this diagram captures a bit of the flavor of the importance of “the tail” behind “the tooth” of innovation discussed in the previous LOTRW post. Even by the 1980’s, at the time this diagram was created, scientists had already amassed an enormous body of knowledge about the Earth system, all of which had to be kept in mind while attempting to advance the frontiers further; an updated version of this diagram would look like a Mandelbrot set; the basics would remain the same, but within each box there would be a nested microcosm of equal complexity.

Francis wasn’t simply bright as in “thoughtful, insightful,” though he was both these things. He was also quick and vigorous in debate and, in fact somewhat inclined toward it (all signature-Cambridge traits, though it’s hard to determine whether Cambridge creates this attribute or simply attracts it…).

Proceed to positive energy and enthusiasm. Francis loved science and he loved people, and he brought those traits to every conversation with every person and every group. He could, and did, command the attention of the room, no matter how large or crowded. First there was his imposing physical stature. Then there was the shock of red hair. Then there was the penetrating gaze; in conversation, often rendered from inches away – not feet.

Then there was the voice. Ah, the voice! We’ve all heard many speakers claim to not need a sound system – but Francis truly didn’t. His voice carried.

But what made the voice powerful, the time with Francis memorable, whether in big crowds or small, truly memorable was his vision, and his crisp, powerful exposition of big ideas. It was impossible to be with him, even in a crowd, and feel detached. Everyone within the sound of his voice would be fully engaged – a participant, a collaborator, not a bystander. For those few moments, we would actually all be a little brighter, a bit closer to the top of our game.

Which brings us to leadership style. When Francis was offered the NCAR/UCAR positions, some people wondered: why offer such a vital, pivotally important leadership role to anyone, no matter how bright, whose only previous management experience was in a faculty position at The Johns Hopkins University where he mentored no more than five or six graduate students at any given time? But Francis put that experience to work, to good effect. He simply ran NCAR/UCAR the same way. Only, now he had 500-600 “graduate students.” Four days a week he would walk around, assigning thesis topics to early-, mid-, and senior-level scientists alike (he was equal opportunity). Fridays he would do his own research. Somehow it worked. And worked well. Several generations of management later, it’s still easy to spot the Bretherton DNA across the activities and vibeof the place. The authority he carried there (and wherever he would later find himself) was always the power of his ideas, not his position on any organization chart.

The American Meteorological Society is indebted to Francis in many ways. One (very small) example: In 1976 the AMS was standing up a new STAC Committee, this one on Atmospheric and Oceanic Waves and Stability (today’s Committee on Atmospheric and Oceanic Fluid Dynamics). Francis joined Owen Phillips and Jule Charney to get the first conference, held in Seattle, off to a good start. He delivered the keynote. Two hundred people showed up for the meeting, in large part to hear from the three of them. The committee and the AMS fluid dynamics community continue to be vibrant and active, almost fifty years later.

Now that’s what it means “to make the world a better place.” Thank you, Francis.

Francis was one of my two Ph.D. committee members at Wisconsin who served from start to finish, a long and winding road. In retrospect, I should have found a way to spend more time with him, but it’s easy when you’re a student *not* to seek out opportunities to reveal your ignorance to brilliant people. (Moral: students, dare to be stupid with your professors. That’s how you learn.) When I attended a summer school in geophysical fluid dynamics at Cambridge in 1992, I made sure to go to the departmental library and look up Francis’s dissertation. It made me feel a little better that the equations in his dissertation were handwritten; I guess I had expected them to be carved in stone, like the Ten Commandments!

Francis was also very kind and not judgmental when my wife Pam quit her Ph.D. (which was the best decision of her life, setting her up for a career in outreach and extension in climatology that suits her perfectly). He is missed.

Thanks so much, John, for this reflection. Good to hear from you on any subject, but especially in this vein. continuing best wishes.

Bill- a wonderful post. I only knew him by reputation but this post gave me a great insight. Thank you. Mary

Dr. Hooke

Do you mind if if tweet this giving proper credit. I would have loved to have made acquaintance with this scientist. James henderson

You’re welcome to do so.