another guest post from George Leopold…

We finally threw in the towel during a recent East Coast heat wave, closed the windows and turned on the air conditioning. Despite some nighttime cooling, our upstairs was getting stuffy and the fan couldn’t keep up with the persistently warm fall weather.

That, according to experts who study energy usage during periods of extreme weather, is pretty much how most of us behave during a prolonged heat wave. “Later days in a heat wave tend to have higher electric demand,” Craig Williamson, an energy analyst with EnerNOC Inc. told a recent AMS Policy Program briefing on the impact of heat waves on the nation’s energy grid and public health.

The prevailing attitude, according to Williamson, is that consumers can bear the heat only so long before they opt to crank up the AC. Williamson called it the “heat build-up effect,” especially for residential users.

With peak energy demand shifting into the evening, utilities are leveraging emerging grid technologies to help manage fluctuating demand. As average temperature rises, so too has electricity demand as more consumers install central or window air conditioners. Williams estimates that nearly 20 percent of residential power is now used for cooling as more homes install AC.

The ubiquity of air conditioning in the United States is being driven by the same market and technology forces that have greatly reduced the cost of consumer electronics. You can now purchase a window air conditioner made in China for about $100. I’ve even seen them for sale at grocery stores. (Interestingly, most urban Chinese do not own air conditioners.) The problem, according to Williamson, is that window units use more electricity than central air conditioning.

The slow but steady rollout of the smart grid here and around the world is helping to offset at least some of the effects of extreme weather. “Smart grid technologies can identify problems more quickly, and minimize the negative impacts” of heat waves, including rolling blackouts, Williamson said.

And despite all those little green lights we see in our homes at bedtime, experts note that energy efficiency programs targeting household appliances and other energy hogs have helped reduce power demand. Proof once again that conservation remains an energy source.

Then there are the public health effects of heat waves, especially in urban areas. John Balbus, an MD and senior advisor for public health with the National Institute of Health’s environmental health sciences unit, told the AMS briefing that the increasing frequency and severity of heat waves has resulted in more heat-related illnesses and deaths.

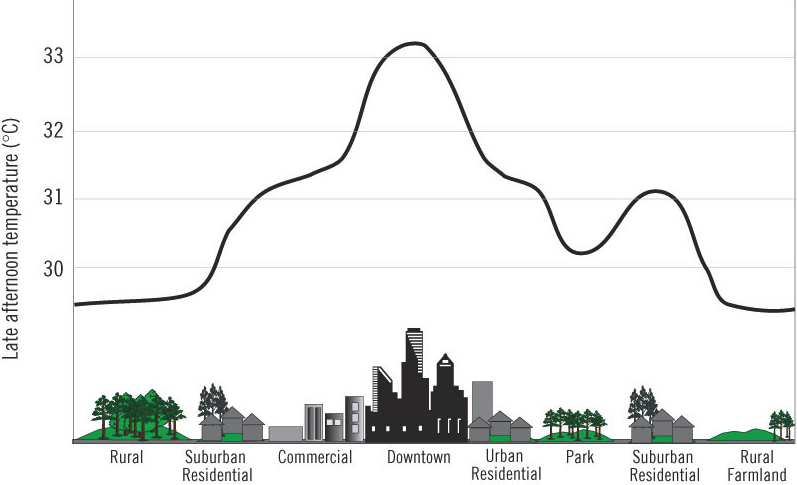

At greatest risk are residents of poor urban areas with limited access to air-conditioning. Matters are made worse for the urban poor because the growing frequency of heat waves has spawned urban “heat islands” in many U.S. cities. All that concrete and asphalt is re-radiating heat that builds up during summer afternoons, inhibiting cooling in the evening.

The more concrete, the more heat. (Source: EPA)

U.S. cities like Chicago are attempting to tackle the heat island problem with green roofs and other mitigation efforts. Any new structure built with public money in Chicago must now include a green roof, city law requires. Balbus cited the results of a recent study that found increased tree canopies help to reduce the urban heat island effect.

The lesson here is that passive cooling techniques like tree shade and lowering the blinds in the afternoon can help limit the worst effects of heat waves on humans as well as the power grid, the critical infrastructure we take for granted until the lights – and the AC – go out.

-30-