Be the change you want to see in the world. – Gandhi

In their hearts humans plan their course, but the LORD establishes their steps. – Proverbs 16:9 (NIV)

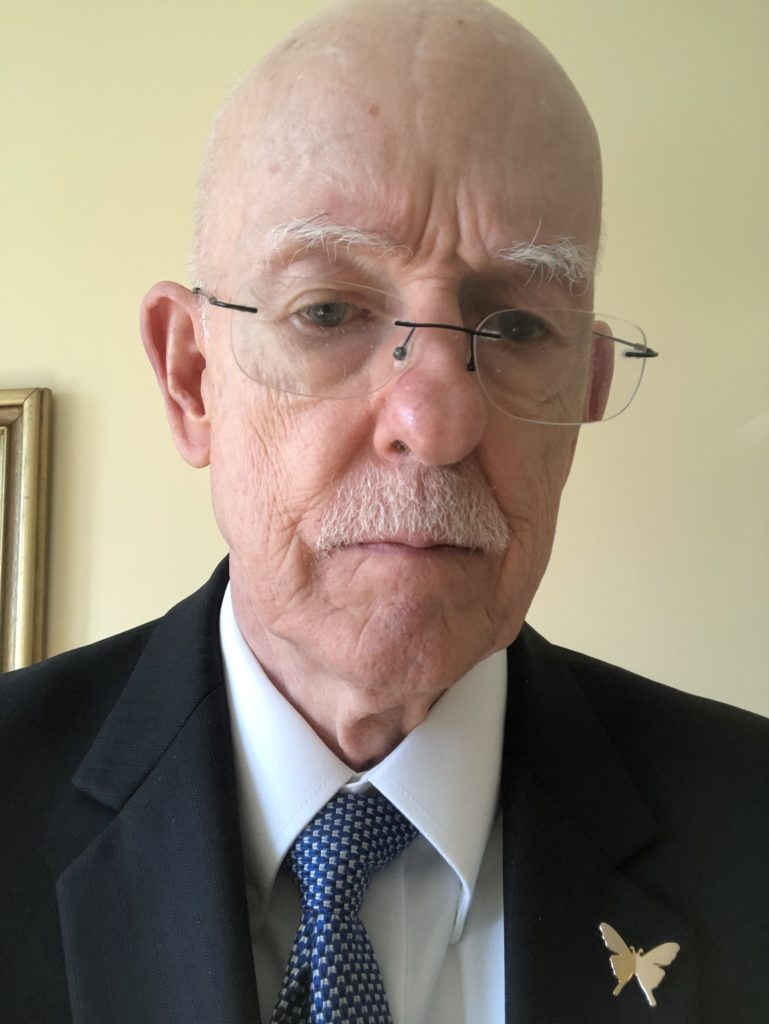

Had a meeting in D. C. last week – my first foray downtown in quite a while. Felt good! But meant I had to find my suit and tie (pictured). I call your attention to the butterfly in my lapel.

Have taken to wearing that lately. (You didn’t ask, but) here’s why.

Central idea is that wonderful metaphor of the Lorenz butterfly. Wikipedia tells us:

In chaos theory, the butterfly effect is the sensitive dependence on initial conditions in which a small change in one state of a deterministic nonlinear system can result in large differences in a later state.

Lorenz and his meteorological colleagues provided a mental picture: a butterfly, minding its own business and fluttering about, can set into motion a growing disturbance that might generate a hurricane half a world- and weeks downstream.

The idea stuck. It has become the starting point of meteorologists’ stock rebuttal to all those folks who complain that weather forecasts aren’t that great.

But perhaps Lorenz’ butterfly is a metaphor for life itself. Some reflections:

First, our individual lives and actions matter. Very cool! We yearn to make a difference. We hunger for our lives to have meaning. Gandhi’s profound quote speaks to this primal need and actually shows us how to satisfy it. he tells us that the greatest way for each of us to drive change – perhaps ultimately the only way we can make a lasting difference – is through our core character and nature. If and when we try to force change on others our efforts will (and should) fall short.

But we can’t fake it. If we change our own behavior, but it’s only an act (recall the original Greek word for actor was hypocrite), we fail to achieve the desired result. The only real and lasting influence on others or events that we have stems directly from our true essence, our being – nothing less. If others find that attractive, they’re inspired to follow suit and our influence will grow. If not, our impact will wither away.

It’s possible to sleepwalk through our reflection on this and only get part of the message – to conclude that Gandhi was right, but that he was at the same time implying that we should be satisfied with having some small individual-scale influence, not one that is earthshaking.

This is where the butterfly flutters in. Gandhi was going big. He was hinting that society, like the earth’s atmosphere, has attributes of a chaotic system. He was saying something more like: if you can master and hold fast to the needed or desired change in yourself, then that change can grow to become a reality of the larger world outside. In fact, that may be your only path to initiating big change.

Second, we’re superior to that butterfly. We’re aware and intentional about the big picture, and what we want to accomplish in that larger arena. The butterfly’s fluttering reflects a search for food, aquest for a mate, eons of Darwinian programming and the resulting bits of DNA – no more. In some but not all cases the butterfly may be migratory; it’s fluttering may have direction. But the butterfly is living in the moment. That distant hurricane is never on its mind. It has no idea whether its movements are generating such an extreme or ameliorating one. (Is its problem ignorance, or is it apathy? The butterfly doesn’t know and it doesn’t care.)

(That saves the butterfly a lot of frustration. Because in chaotic systems such as the Earth’s atmosphere, not all places and times are equally responsive to small changes in the initial conditions. Only occasionally will a given butterfly find itself in a position of influence.)

Natural to feel smug in comparison. We humans can conceive of and hold to larger aims and purposes, and we are self-aware. We can see our progress towards these life goals – or instead know that we’re experiencing a rough patch – floundering about or even losing ground. We have a sense of which way we want things to go, and which way our world is tending. And a large part of being the change we want to see in the world stems from the educational path we choose and jobs we take and where and with whom we settle. We can do much to put ourselves in positions where our small contributions can make a big difference.

In the year 2023, when it comes to making a needed difference, we’re in a target-rich environment. The world needs betterment in many ways. A pandemic has shaken populations and ways of life. Recovering economies are fragile, struggling to cope with inflation and labor shortages. Meanwhile, food shortages loom. The environment, habitats, and biodiversity are on the wane. Inequity and injustice are rampant. War, terrorism, and violence wrack every continent; major actors like China and the United States are saber-rattling (and drawing other nations in). Autocracy is on the rise; democracies seem to be heading in the other direction. Given the vast scale and ubiquity of these woes, it’s easy to start (and easy to end each day depressed).

Together Gandhi’s wisdom and the butterfly’s exclamation point show us a path forward and give us hope.

But not so fast…

A third, more sobering aspect: intentionality itself has its limits. A small example from literature; Wikipedia tells the story:

The Jungle is a 1906 work of narrative fiction by American muckraker novelist Upton Sinclair. Sinclair’s primary purpose in describing the meat industry and its working conditions was to advance socialism in the United States. However, most readers were more concerned with several passages exposing health violations and unsanitary practices in the American meat-packing industry during the early 20th century, which greatly contributed to a public outcry that led to reforms including the Meat Inspection Act.

Scholars have generalized this dilemma in what is they call the intentional fallacy, saying “the design or intention of the author is neither available nor desirable as a standard for judging the success of a work of literary art”. How bad does this get? In our pessimistic moments, we speak of good intentions as “paving the road to hell.”

It doesn’t take much imagination to see similarities between the public’s reaction to warnings about climate change and its risks and the unanticipated, redirected uptake a century ago in response to Upton Sinclair.

Fourth: maybe, just maybe, there’s a Higher Level of Intentionality at play. This is not a new idea; it’s goes back a long way, some 2500 years or more. Proverbs 16:9 (quoted above) makes clear that the people of that day (and place, the Middle East) were quite aware of the limits of intent. They saw it as the result of a hand of a Higher Power – God as they understood him. Taken by itself, the quote speaks of God’s final say without a judgment on whether that final say is a good or bad thing. But the larger context of the dozens of other proverbs and the Old Testament itself suggest they saw a God who favored plans aimed at equity, fairness, and general benefit, while working against plans to do evil. This picture of God expanded considerably as a result of later Mideast events memorialized every year since.

Change beginning requiring no more of us than merely remaking our individual selves? Change “going viral” in that deterministic nonlinear system we call society, and thus remaking the world – for the better? Reasons for hope this Easter weekend.

I have been irked by the use of the Butterfly Effect in mainstream/culture ti warn of (always) how big bad things happen because a little bad thing was allowed to happen. I argue the principle is not relevant to life except under the situation of a “tipping” point already in place.

Example: you flip a switch and all the lights in your house come on. We have to have 150 years of technology and electricians wiring your house for this minor force to do anything.

In opposition: all accident/Mayday reconstructions show that planes crash etc nit because someone spilt a cup of coffee on the instrument panel, but because the pilots were both distracted by a signal the wheels weren’t coming down, and didn’t watch altitude, they were flying in fog/cloud, the ground controllers didn’t alert them their holding circle had drifted toward the mountains and they had set autopilot at an altitude lower than the mountaintop (Japanese event).

1. Multiple events must line up for a small input to have a large output.

A strong wind will blow every Butterfly out to sea, along with the chain of events the wing beat caused.

2. Strong events completely negate large events.

A Butterfly wing beating doesn’t make a bowling ball move a tiny bit; the ball doesn’t move at all due to Threshold energy and forces required to overcome static friction or other forces in the real world.

3. Threshold forces must be reached outside of things freefalling in the vacuum of space.

You can dig up a thousand dandelions and there’ll be a hundred next week because a) the soild have developed a two year seed bank and b) your neighbors upwind garden is a dandelion freeway.

4. There are multiple forces in the world that are repetitive and directionally consistent with sufficient power to overcome small influences.

I get this Butterfly Effect argument from my New Age Sensitives. “The world is an interconnected sensitive place! We must be SO careful!”

Of course I make no impact: feelings and good intentions trump reality.

🙂 Thanks for this extended comment (or set of comments). Lot of food for thought here, and much to like, including some of your examples.