WWCPD… what would Colin Powell do?

There’s war in the air these days. The U.S. and Korea are at loggerheads. With great fanfare, Putin brags that Russia is developing nuclear arms able to avoid missile defenses. China is rapidly building and deploying its military, projecting power throughout the western Pacific and the Indian Ocean, with one eye on the Arctic. Syria has attracted warriors from Turkey, Iran, Russia, and the U.S. in a particularly combustible mix. Pockets of conflict burn across the African continent.

The language of war has penetrated everyday discourse. Financial markets worldwide have been fidgety at the prospect of tariffs and “trade wars.” There’s a “war” over gun-control. Then there’s immigration. Attorney General Sessions grumbles about sanctuary cities, and California’s Governor Jerry Brown has responded by saying the Trump administration was declaring war against the state.

This brings us to the war on science. For instance, writing in the Chronicle of Higher Education (unfortunately not accessible without a subscription), Steven Pinker has decried an intellectual war on science he says is wreaking havoc on research. (The article has prompted some publicly accessible commentary; here’s one example.) Climate change denial is framed as a war on humanity. Scientists appear to be entering the 2018 political arena in record numbers, “to combat the war on science.”

As individuals and as a species we’re pugnacious – quick to see a fight or pick one – and especially quick to use the rhetoric of war.

What could possibly go wrong?

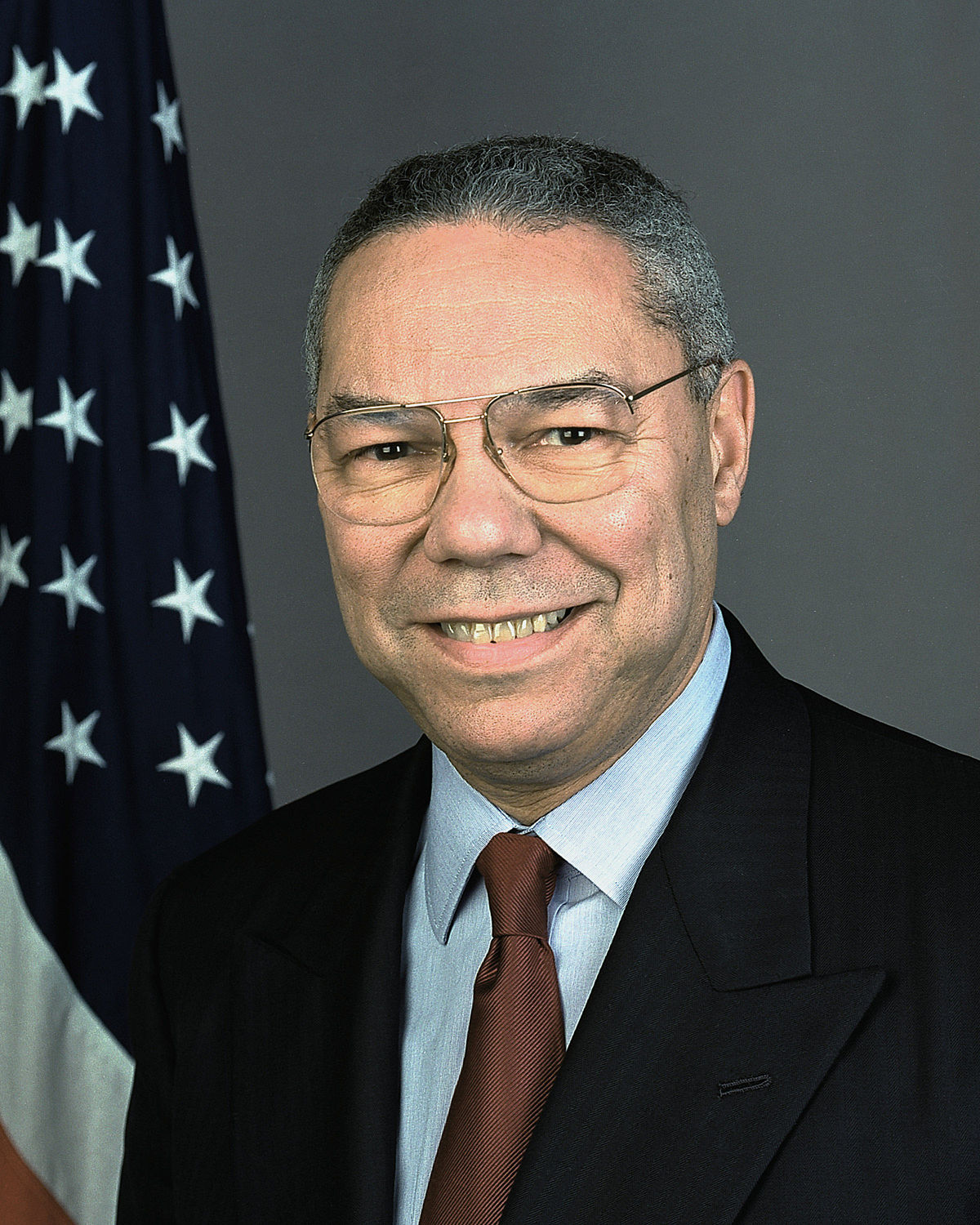

Interesting that the folks most familiar with war and its horrors should be the most measured in the use of such language and the most reluctant to engage – the military. The military know that war should only be entered as a last resort, after all alternatives have been exhausted. This seemingly counter-intuitive bent has always been around, but it was articulated with special poignancy by Colin Powell prior to the first Persian Gulf War[1], in eight famous points now known as the Powell Doctrine:

The Powell Doctrine offers a list of questions that all should be answered affirmatively before military action is taken by the United States:

- Is a vital national security interest threatened?

- Do we have a clear attainable objective?

- Have the risks and costs been fully and frankly analyzed?

- Have all other non-violent policy means been fully exhausted?

- Is there a plausible exit strategy to avoid endless entanglement?

- Have the consequences of our action been fully considered?

- Is the action supported by the American people?

- Do we have genuine broad international support?

As a corollary, Powell also argued that once embarking on a war a nation should use all its resources to achieve decisive force against the enemy, minimizing casualties and ending the conflict quickly by forcing the weaker force to capitulate. Implicit in this, especially the word capitulate, is the idea a nation goes to war or uses the rhetoric of war only against actual enemies, not just people with whom it might normally collaborate but with whom it’s currently estranged or in disagreement.

The application of the eight questions to war itself is clear enough, but in our polarized, fractious society of today, perhaps we’d all do well to ask whether we might think them through more generally and thoroughly before entering confrontation over policy or even scientific debate. In those contexts, we might ask:

- Is a vital national security interest threatened? Or are we making a mountain of a molehill?

- Do we have a clear attainable objective? Something a bit nobler than “winning” an argument?

- Have the risks and costs been fully and frankly analyzed? This answer is hardly ever “yes.”

- Have all other non-violent policy means been fully exhausted? Again, the answer is rarely “yes.”

- Is there a plausible exit strategy to avoid endless entanglement? Or will hard feelings endure?

- Have the consequences of our action been fully considered? Highly unlikely. After needed further consideration – we should revisit (3.)

- Is the action supported by the American people? We should be hesitant, humble answering this one. Scientists in particular should avoid appearing entitled.

- Do we have genuine broad international support? Or – are we simply damaging our/America’s reputation?

Going a step further: implicitly, we all ask ourselves questions similar to these when engaging our spouses/life partners/parents/kids. If we choose to go to war at home, we’re usually using it as an excuse/pretext for busting up the relationship.

Note that according to Powell, all these questions should be answered affirmatively before going to war. A meteorological parallel: when I worked for NOAA in our Boulder laboratories, one of my colleagues was a wonderful meteorologist and great human being by the name of Charlie Chappell. His work spanned both cutting-edge research and operational practice. He used to say that “for the atmosphere to generate a tornado, seven conditions must be met. A lot of meteorologists become excited when they see six conditions satisfied, and they issue a warning that turns out to be a false alarm. All seven conditions have to be met.”

So, next time out, before we go to war verbally, or take to the streets in protest, let’s stop and consider whether we’ve thought things through, what we’re hoping to gain, Chances are good that if we’re as creative in thinking about alternative peaceable means as we choose to be about “waging war,” we’ll “give peace (another) chance.”

As we support our fellow scientists who are running for political office, or as we run for office ourselves, let’s engage in a positive spirit about both the process and the ends of politics. Let’s do it not thinking the political process would be improved by putting more scientists in charge so much as aspiring to put ourselves to work for public benefit.

And everyone – all parties, and the watching world – will be the better for it.

____________________________________

[1] reflecting the bitter U.S. experience in Vietnam,